How to develop a sourcing strategy.

Build or buy? Contract or in-house? Offshore or domestic? Whom should we hire?

Firms face these questions every day. Smart managers often have an underlying philosophy that influences their choices, maybe something about "core competencies" or "not-invented-here syndrome". Many firms will at the very least consider these questions when debating the annual budget. But relatively few organizations have a conceptual framework, let alone an articulated strategy, in place to guide their sourcing decisions on a day-to-day basis.

Organizational planning? That's for HR. Let's just do whatever is fastest and move on to the next thing.

If you're the kind of person that's influenced by quotes, here's a couple of juicy ones:

"Quite simply, strategic sourcing is the most powerful tool a company can deploy to unlock profit, with a return on investment that is measured in the hundreds of percent and payback in months" - Stonebeck (2009)

and:

"Historically, many firms have made sourcing decisions [...] based disproportionately on unit cost, with insufficient regard for strategic or technological issues. This cost-focused approach has led to competitive tragedy for many firms, indeed entire industries. Managers need better tools for evaluating source decisions--tools that can accommodate the long-term, strategic issues" - Welch and Nayak (1992)

But "strategic sourcing" doesn't have to be complicated or require a million-dollar consulting project. Your team probably has the knowledge and information necessary to develop a sourcing strategy---after all, they're making these decisions already. What you're missing is a framework by which to organize and communicate your sourcing strategy. It's not hard. This article will show you how.

Contents

This article is organized into four parts.

If you are impatient you can jump ahead to the process definition.

If you're confused by what you find there, it may be helpful to review some of the background concepts first.

1) Objectives

Beginning with the end in mind, let's take a moment to define what it is that we're trying to create.

What we're ultimately after is smarter (and possibly faster) decisions around how to procure or develop the services, skills and materials we need to get our real job done. This is sometimes called "strategic sourcing". Specifically,

Strategic Sourcing : is the process of taking deliberate action to improve procurement processes, supplier relationships and capability development in order to optimize the supply chain.

To reach our objective of optimizing the supply chain, we'll need a framework---or better yet, a plan---that we can use to identify and guide those deliberate actions. Hence, the

Sourcing Strategy : captures the decisions we've made and/or policies we've set to inform and direct our sourcing activity; anticipates the skills, assets and capabilities that are required to meet our future needs; and articulates a plan for acquiring or developing them.

2) Background

Before describing the process for creating a sourcing strategy, let's first set the stage by reviewing a few key concepts.

2.1) Understanding sourcing

When I first introduce this concept to an organization or team, someone inevitably jumps to the conclusion that "strategic sourcing" is a euphemism for "outsourcing". Not at all.

First, one of the most beneficial artifacts that emerges from this process is some form of capability development plan, a roadmap that describes how to hire new or train existing staff to ensure the organization has the capabilities it will need in the future.

Second, the decision to outsource a capability or function is just the first of many. We then need to determine how we want the capability supplied, which vendor, what our relationship to the vendor must be, etc.

Consider the ways your organization might obtain a given service or function:

- You could do it "in-house" (i.e., with employees).

- You could hire external contractors that extend the in-house capabilities, but are managed very much like employees.

- You could pay a firm to deliver the service (so you don't have to manage the work directly).

- You could form a partnership with another organization that would share in the success or failure of the venture.

- You could take go online and use your credit card to sign up for a SaaS product without every directly talking to another person.

- Etc.

There are many different ways to acquire a product or service, and many different relationships you might have with the supplier. The question isn't "in or out?" but "how far in or how far out?"

To better understand our sourcing options, let's explore two aspects of the decision:

What kind of supplier are we looking for?

What kind of relationship do we want to form with that supplier?

2.1.1) The supplier type spectrum

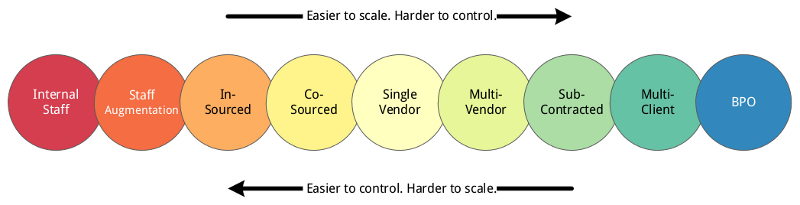

Looking at a spectrum from "most intimate" to "least intimate", we might identify 9 different ways of sourcing a given capability or function:

- Internal Staff -- the service is provided by employees.

- Staff Augmentation -- the service is provided by contractors or freelancers that are managed very much like direct employees.

- In-Sourced -- the service is developed by an external supplier, but brought "in-house" for ongoing operation and maintenance. (A lot of enterprise software implementations work this way, for example.)

- Co-Sourced -- the service is collaboratively developed and maintained by a combination of an external supplier and internal staff.

- Single Vendor -- the service is developed and maintained by a single external supplier. (This is a pretty typical supplier relationship.)

- Multi-Vendor -- the service is provided by multiple suppliers, organized or coordinated by the firm itself.

- Subcontracted -- the service is provided by a "primary" supplier of some sort, who is in turn relying on subcontractors to do the work.

- Multi-Client -- the service is not customized for the individual firm, but provided by an "off-the-shelf" product of some sort. (E.g., something physically "installed" at the firm's location, or a SaaS-product that serves many clients.)

- Business Process Outsourcing -- an entire business function is delegated to a supplier. (E.g., payroll functions are often outsourced in this way.)

Note that moving up (left) on that spectrum (from "BPO" to "Internal Staff") we have an increasing degree of control over the service, but a decreasing ability to scale the service. We can get staff or freelancers to build or provide exactly what we ask them to (for better or worse), but both the number of employees and the rate at which we can hire them are naturally constrained.

Moving down (right) on that spectrum (from "Internal Staff" to "BPO") we have an increasing ability to scale but a decreasing level of control over the service. It might be difficult to get ADP or Intuit to change their payroll offering just for us, but they can write as many checks from as many accounts as we need without breaking a sweat.

2.1.2) The vendor relationship spectrum

Just as there are many different types of supplier, there are many different relationships we might establish with that supplier. Is the supplier a long-term partner or simply the first vendor we called that had the part in stock?

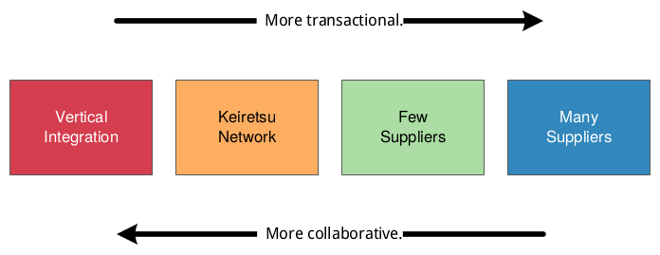

On a spectrum from "most intimate" to "least intimate", here is one simple categorization of vendor relationships:

- Vertical Integration -- the supplier is acquired outright.

- Keiretsu Network -- multiple suppliers are integrated into a collation of interconnected companies (cf. Wikipedia's article on the term "Keiretsu").

- Few Suppliers -- long-term "partnerships" are formed with one or a few suppliers.

- Many Suppliers -- shallow relationships are formed with many interchangeable suppliers, and we switch between them frequently.

At the bottom (right) side of this spectrum are the "commodity" suppliers. For example, we could probably buy the same pencils from many different vendors, and the "switching cost" is very low. Our choice of vendor will be driven by other factors, such as price or quality of service.

At the top (left) side of this spectrum are strong partnerships (sometimes literal partnerships) formed with unique or critical suppliers. Apple, for example, designs its own hardware, develops much of the software that runs on it and controls many of the retail outlets at which these products are sold.

2.2) Visualizing a sourcing model

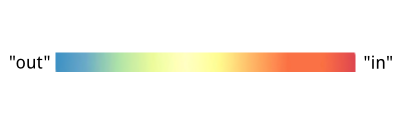

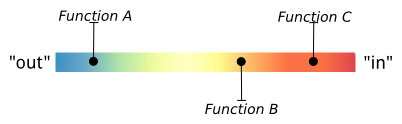

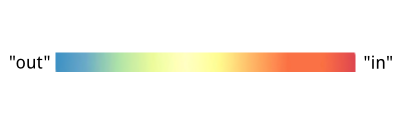

Based on factors such as the way in which a function is supplied and the relationship between the firm and the supplier we can imagine a simple scale with fully "delegated" services at one end and fully "integrated" services on the other. Continuing the color scheme used above, that scale might look like this:

We can create a diagram of a given sourcing model by simply pinning each "function" (i.e., service, resource or capability) to the appropriate point on the scale:

At a (very) high level, a sourcing strategy might be captured by a "current" and "desired" version of this diagram, and a plan for how we get from here to there.

(We'll use a variation of this diagram when we build our sourcing strategy below.)

3) The process

Developing a sourcing strategy doesn't need to be difficult.

In this section we present a six step plan for creating a sourcing strategy:

- Enumerate the "things" you need to source (functions, services, resources, capabilities, etc.).

- Document your current sourcing model.

- Determine your desired sourcing model.

- Use the information gathered in steps 2 and 3 to visualize how well your current sourcing model matches your desired sourcing model.

- Determine what to do about the "deltas" that you discovered in step 4.

- Develop an execution plan for doing it.

At the end of this process you will have:

- A quantitative analysis of your sourcing needs.

- Documentation of your current sourcing model.

- A description of and rationalization for your desired (future) sourcing model.

- A plan for transitioning to your desired sourcing model.

- Some tools that might help you communicate all of these things.

The following sections walk you through each step of the process.

Step 1: Enumerate the things to be sourced.

We need to create a list of the functions, services, resources, capabilities, etc. that we intend to include in our sourcing strategy.

There are many ways to go about this. Two relatively straightforward ones are:

Think about the skills or competencies your team has now or might need in the future. For instance, a web-based company might currently have project management, graphic design, web design, web development and server hosting capabilities, and anticipate a growing need for user experience design, mobile app development and quality assurance capabilities.

Think about the vendors you currently do business with and the staff you currently employ. What services are you paying for? What roles do your staff fulfill? For example, maybe that web-based company hires freelancers to redesign the website when needed and hosts the website "in the cloud", maybe through Heroku or AWS.

Step 2: Document the current sourcing model.

(For the sake of convenience, we'll call the "things" we've chosen to include in the strategy "functions".)

Review the functions you identified in step 1. For each item on the list we'll want to answer two questions:

On a scale of 1 to 10, how "intimate" is our relationship with the supplier of this function? For example: If the supplier is an employee, we might rate this function a 10. If the supplier is a mass-market SaaS website, we might rate this function a 1.

How much are we currently spending on this function? Note that this should include both "hard-dollar" expenses (payments to external suppliers) and "soft-dollar" expenses (staff time).

We should end up with simple spreadsheet that looks something like this:

| Function | Current Relationship | Investment |

|---|---|---|

| Staff Cafeteria | 8 | $13,235 |

| Water Service | 3 | $2,667 |

| Shark Food | 5 | $4,506 |

| Shark Trainers | 7 | $28,294 |

| Laser Canon R&D | 10 | $9,873 |

Step 3: Determine the desired sourcing model.

Run down the list of functions you identified in step 1 again. This time we'll answer two more questions:

On a scale of 1 to 10, how critical is this function to our business? Is this something we could live without (a vending machine in the breakroom, perhaps) or something that without which we would cease to operate (electricity and phone-lines, for example)? Does this function support our flagship product, or is it in service of some side-product we launched because it brought in a little extra revenue and we could do it?

On a scale of 1 to 10, how distinctive is this function for our business? Is this some commodity for which our needs are the same as everyone else's (like photocopier maintenance in most offices) or is this an important part of our brand identity or a significant source of our competitive advantage (the way in which customer service is for Zappos, or user experience is for Mint)? Note that it's entirely possible for a function that is common for most businesses to be a distinctive characteristic for our business.

Coupled with the data from step 2, our spreadsheet now looks like this:

| Function | Current Relationship | Criticality | Distinctiveness | Investment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff Cafeteria | 8 | 5 | 4 | $13,235 |

| Water Service | 3 | 8 | 3 | $2,667 |

| Shark Food | 5 | 9 | 6 | $4,506 |

| Shark Trainers | 7 | 7 | 8 | $28,294 |

| Laser Canon R&D | 10 | 10 | 10 | $9,873 |

Step 4: Create a visualization.

Recall that "rainbow sourcing scale" we constructed a little while ago:

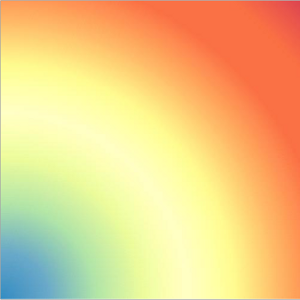

Imagine a two dimensional version of that:

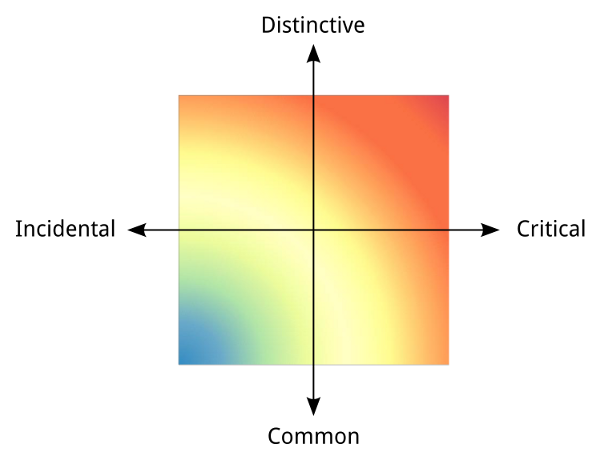

Now add axes for the "critical" and "distinctive" dimensions we evaluated above:

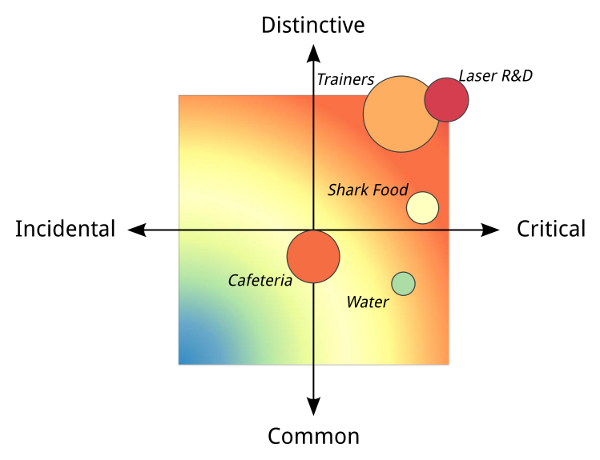

Now plot the current and desired sourcing model on that chart, using the following rules:

- Each function will be represented by a "bubble" on the graph.

- The X and Y coordinates for the center of each bubble are determined by the "Criticality" and "Distinctiveness" ratings identified in step 3.

- The area of each bubble is proportional to the level of investment in that function, as identified in step 2.

- The color of each bubble is determined by mapping the "Current Relationship" rating (identified in step 2) to our "rainbow sourcing scale". (For example, a rating of 10 would be red, a rating of 1 would be blue, a rating of 6 would be a yellow-orange color).

For our example data above, that diagram looks something like this:

Now we have a succinct visual representation of our current and desired sourcing model. (We'll discuss how to interpret it in the next step.

Step 5: Evaluate.

As garish as it might be, the bubble chart we created in step 4 packs a lot of useful information into one image.

One of the most useful aspects, for our purposes here, is the contrast between the color of each function-bubble and the color of the background gradient at the same point.

Where the colors are the same (or similar), there is a close alignment between our current method of sourcing that function and the desired method of sourcing, according to our strategy.

Where the colors are different, our current method of sourcing that function is different than what we'd like it to be.

The larger the bubble, the more money we're investing in the supplier, so our attention should probably first turn to large, high-contrast bubbles.

Interpreting the chart

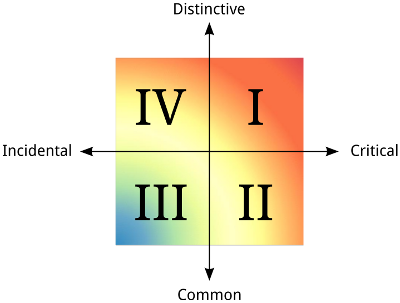

Let's step back for a moment and think about what the bubbles on that chart really mean. We can divide the chart into quadrants:

- Quadrant I: Distinctive and Critical

- Quadrant II: Common but Critical

- Quadrant III: Common and Incidental

- Quadrant IV: Distinctive but Incidental

General strategic principles

As a general rule:

- We should focus our time on the items that set our business apart from the competition, and

- We should focus our money on the items that are critical to our business operation.

Hence we should expect to see the larger bubbles on the right side of the chart and the "redder" bubbles at the top of the chart.

More specifically:

Quadrant I: Distinctive and Critical : Items in Quadrant I were ranked as being both critical to our operation and an important differentiator for our business. This is where we'd like most of our bubbles to be. For items already in this quadrant, we might want to look for additional ways to build on or exploit them to create even more value.

Quadrant II: Common but Critical : Items in Quadrant II were rated as critical to our operation, but nothing special for our business in particular. They are likely to be basic infrastructural services that are critical to everyone's business. It would probably be nice to reduce the size of these bubbles, but this is not an area where we want to trade quality for a lower price.

Quadrant III: Common and Incidental : Items in Quadrant III were rated as neither important nor unique to our business. We might reconsider whether we want to do these things at all. If any bubbles remain here, we should make them as small as possible.

Quadrant IV: Distinctive but Incidental : Items in Quadrant IV are often the most difficult to deal with. These are the things that we do well--they set us apart from other organizations--but that aren't particularly important to our business. We should probably (A) stop doing them altogether or (B) find a way to make them more valuable to our business. But this can be difficult in practice. Option A is a delicate situation politically (as staff are probably emotionally invested in the work). Option B is probably difficult (otherwise we would have done it already).

Some tactics

The strategic model diagram can tell us where the current approach to sourcing is out of alignment, but it can't tell us specifically what to do about it.

For each item that seems out of place, we'll need to decide how we want to address it. This is where our creativity and strategic thinking comes into play.

Let's look at some ways we might effect specific types of change:

To move a bubble to the right on the chart, we need to make it more valuable to our business. For example, we could:

Attempt to grow the revenue lines that this function supports, increasing our ROI on the activity.

Look for new, possibly radical ways, to create new revenue lines from that function. Are we good at web design? Maybe we should rent our designers out like an agency. Do we run the world's largest online bookstore, and need excess capacity to handle the holiday rush? Maybe we should rent out our processing power during off-peak periods.

Look for similar or complementary functions that we could diversify into (whether directly, or though a vendor or via a partnership).

To move a bubble to the left on the chart, we need to make it less important to our business. For example, we could:

Sunset the products or services that the function supports.

Find a way to substitute some other function for this one (in the place that we use it).

Put the function on a kind of "autopilot"--reducing investment and keeping the product line it supports as long as it remains easy and profitable to do so.

To move a bubble up on the chart, we need to make it more distinct or unique to our business. For example, we could:

Invest in the function, increasing the quality or efficiency or other dimension of the function enough to separate us from the pack.

Innovate, finding new and interesting ways to either execute or exploit the function. Can a shoe store compete on customer service? Can an accounting package compete on user experience?

Promote the function (in a marketing sense) so that customers recognize the importance and uniqueness of it.

To move a bubble down on the chart, we need to make it less customized to our business. For example, we could:

Change our business processes so that more "commodity" solutions or suppliers can be used in support of this function.

Change expectations so that our staff and/or our customers no longer believe our organization is a unique snowflake in regard to this function.

Look for partners or suppliers that can help us transition from a bespoke solution to a more common one. What are we doing that's different from everyone else in this regard?

To change the size of a bubble, we must increase or decrease the level of investment in that function. We might:

Invest in the function for a little while--making the bubble larger--in order to make the changes necessary to make the function more efficient--making the bubble smaller.

Eliminate production bottlenecks in order to scale up the level of investment (and level of output, of course).

Look for alternative suppliers that offer higher quality or a lower price.

Make a capital investment to radically change the way in which we service that function.

To change the color of a bubble, we must change something about the way in which we procure the function today. We might:

Move left or right on the supplier type spectrum by "in-sourcing" or "outsourcing" the function.

Move left or right on the vendor relationship spectrum by working more or less closely with the current supplier.

Look for alternative suppliers that are more appropriate for the kind of relationship we expect to have with respect to this function.

An example

Consider the function-bubbles in our example chart. We can readily identify some sourcing arrangements we probably want to do something about.

The Laser R&D function (Quadrant I) seems to be positioned exactly right. We might:

- look for ways to improve the ROI on that function (by getting more value or producing more efficiently), or

- consider whether increasing our investment in the function might be appropriate,

- etc.,

but we probably don't need to make radical changes here.

The Trainers function (Quadrant I) is more or less in the right place, but given the size of the bubble we may want to look at it more closely. We might:

- try to find a way to make that function less expensive (making the bubble smaller), or

- try to find a way to make our organization less dependent upon the supply of this function (moving the bubble to the left), or

- in-source or form a stronger partnership with this supplier (making the bubble "redder"), or

- look for ways to increase the value of the function (moving the bubble to the right),

- etc.

The Cafeteria function (straddling line between the Quadrants II and III) is both off in color and relatively large in area. We should definitely take a look at it. We might:

- try to find a way to make that function less expensive (making the bubble smaller), or

- try to find a way to make our organization less dependent upon the supply of this function (moving the bubble to the left), or

- look for a supplier that we can be less intimately involved with (making the bubble "bluer"), or

- look for ways to exploit the function (moving the bubble to the right), or

- look for ways to innovate in the delivery of this function, making it more a competitive advantage for us (moving the bubble up),

- etc.

The "Shark Food" function (Quadrant I) is important to us, yet we're using a relatively commodity supplier. This might be OK, but it's probably worth a look. We might:

- try to find a cheaper supplier (making the bubble even smaller), or

- look for a supplier that we can form a long term partnership with (making the bubble "redder"), or

- try to find a way to make our organization less dependent upon the supply of this function (moving the bubble to the left), or

- try to "in-source" this function to a greater degree (making the bubble "redder"),

- etc.

The "Water" function (Quadrant II) is even more out of position--critical to our operation but we don't have a close relationship with the supplier. Though small, that's also worth a look. We might:

- find alternative suppliers to reduce our exposure to risk,

- look for a supplier that we can form a long term partnership with (making the bubble "redder"), or

- try to find a way to make our organization less dependent upon the supply of this function (moving the bubble to the left),

- etc.

Step 6: Make an action plan

Having identified the kinds of change we want to make in bring our current sourcing arrangement more in line with our strategy, we should now develop a roadmap or project plan for implementing those changes.

Steps on this roadmap might include things like:

- hiring staff with experience in areas we want to invest or innovate in,

- sending out an RFP to evaluate new vendors,

- meeting with our vendors (singly or in groups) to begin to change our relationship with them,

- sending staff out for training in areas we want to invest or innovate in,

- making plans to sunset products or services that it no longer makes sense to support,

- performing a competitive analysis to find ways to expand or exploit the functions that set us apart,

- etc.

4) Conclusion

That's it. That's all there is to the process.

There are of course much more robust ways to go about any step in this process, but this approach is likely to give you 80% of the value at 20% of the effort.

You should now have:

- A quantitative analysis of your sourcing needs.

- Documentation of your current sourcing model.

- A description of and rationalization for your desired (future) sourcing model.

- A plan for transitioning to your desired sourcing model.

- A garish diagram that might help you communicate all of these things.

The really hard work is still up to you, of course, but now you have a simple process to frame the work that you're doing.

That hard work is also the interesting work, however, so don't be afraid to have a little fun with it or look for creative solutions.